An Aesthetic of Resistance

maximalism and cluttercore, are more than just "trends"

I recently hosted my friends John1 and Paint2 on a Spiral Lab Livestream (available in The Spiral Lab tab, above, as a podcast, or on YouTube as a video), discussing the ways that maximalism and the cluttercore aesthetic exploding everywhere these days (some might say “trending”) specifically suit our neurodivergent sensory peculiarities.

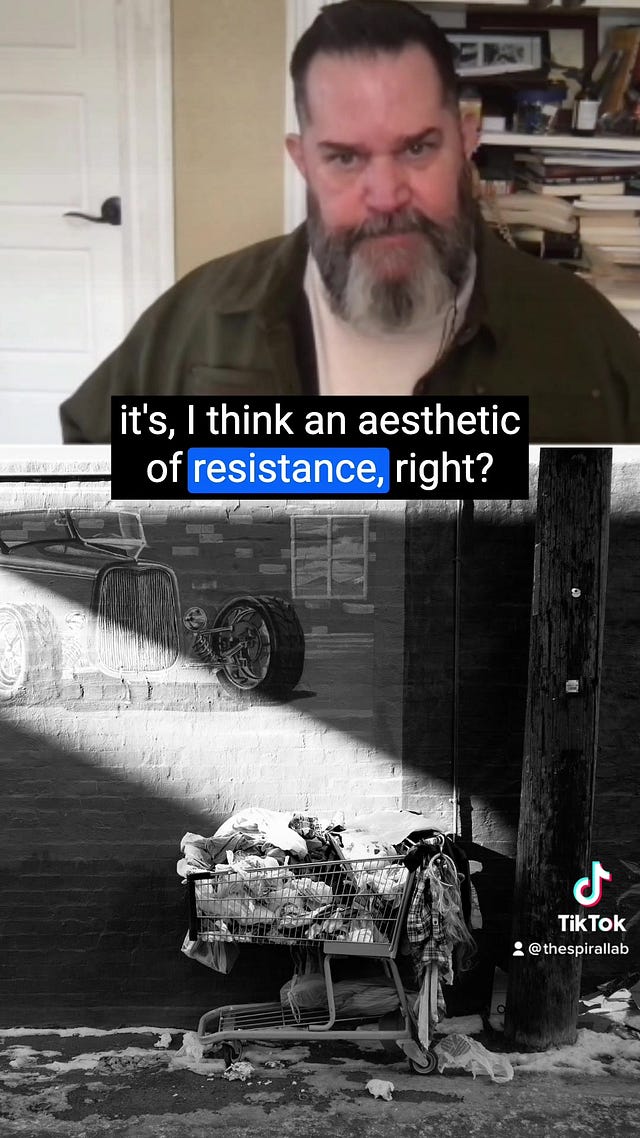

John took the “divergent” nature of cluttercore a step further when he noted that this “principle of design overflows the home space as well. And … oftentimes what you'll see if you kind of work in the spaces where I do3 is this unhoused version of cluttercore; it's, I think an aesthetic of resistance, right? That it's people for whom chaos has won at some point in the far distant or immediate past. And … oftentimes in the way that they arrange the spaces that they don't own and oftentimes are prohibited from entering there's this effort to reclaim chaos in the name of design and livable design, to try to to make equipment for a living out of what would otherwise be just entropy.”

An aesthetic of resistance!

I’m grateful to John for conceptualizing and naming so brilliantly and succinctly something that has been just barely stirring inchaote in my mind for awhile: these “design styles” are so much more than trends! Of course, right now they are also trending (everything ultimately gets coopted—capitalism will eat you for lunch), but I think—especially for many marginalized people (young, disabled, poor, unhoused)— maximalism/cluttercore is both an aesthetic of necessity, but also one of rebelliousness and resistance.

As John notes, among the most marginalized are unhoused people, people who are almost never included as agents in conversations about design,4 but for whom maximalism is both an aesthetic imposed by circumstance, but one that can also be shaped and curated so as to create and reclaim and design space otherwise denied to them.5

I once write a short story about a well-educated, white middle class woman who was not profoundly mentally ill, but who did nonetheless end up without a home and living on the streets; and when it was workshopped the overwhelming feedback I got was that it was “unrealistic” on the grounds that such a fate could never befall such a person. Having spent a fair amount of time among unhoused and near-houseless people (and perhaps knowing on some level—without yet having the language of disability to articulate it—that it absolutely could happen even to me), I knew they were wrong. So many of us live with all sorts of precarity. Unprecedented numbers of young adults are living with their parents, and it’s not just a holdover from pandemic lockdowns when some families decided to bubble together. No matter how much pundits and politicians are pushing a young-people-these-days-are-lazy-and-entitled narrative, I know better. I hope you do too.

It’s a hostile and unsafe world to be coming of age in right now. Especially if you are disabled. For so many of us (and not exclusively young people, of course, but I think especially, as a cohort, young people are disproportionally affected) the very notion of home has become destabilized. Chaotic. Precarious. Unsafe. Whether your are unhoused, living at home, surfing friends’ couches, or scraping by in a depersonalized, overpriced greize apartment, perhaps what you have, again in the words of John, is “what you build out of the chaos. There are times when chaos wins whether you want it to or not, it's not your decision, it just does. And you can either try to abolish it, just clean, truly clean house and make everything adhere to some kind of rational scheme. Or you can work with the chaos in recognition of the fact of contingency and history and life.”

I think the impulse to curate the things we love, the objects that tell our story and give us comfort, that imbue what spaces we are allowed to inhabit with meaning—this impulse is profoundly human. It is homemaking at its most basic. And when disability, poverty, or any number of other circumstances leave us with little agency when it comes to our very homes, this maximalist/cluttercore impulse is, indeed, an aesthetic of rebellion and resistance.

If you would like to see and/or hear the entire conversation among me, Paint, and John, you can find the livestream video here, or the podcast in The Spiral Lab tab in the navigation menu above (or anywhere you listen to podcasts!)

A quick note about The Spiral Lab YouTube Channel and podcast: As we work out the contours of this latest iteration of our YouTube channel, Jesse and Gray and I are especially eager to find a schedule that is both consistent and sustainable. While the conventional wisdom is that you must post every week in order to grow, we also know that can be a grueling upload schedule, even when there are three of us! So our current plan (always subject to change!) is to take off one week out of every four, and as best we can offer either a video or livestream the other three Thursdays. Today is our first official Thursday off!

We’d love for you to take this week as a catch-up yourself, and go view some of our previous videos and livestreams.

And while you’re over there at The Spiral Lab, it would help us enormously if you would subscribe to the channel!

John is a writer, rhetor, teacher, street photographer, and antipoverty activist, born in NYC and living now in Denver, CO. He recently survived a stroke, which took with it a not insignificant chunk of his sense of proprioception. More recently, he was diagnosed with ADHD, which has occasioned a sometimes overwhelming, sometimes exhilarating, almost always exhausting process of re-understanding why and how he is who he is. John wrote a piece about his antipoverty activism here: https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/blog/sh... And he’s collected some of his street photography and found poetry here: https://tiedemann.exposure.co/lost-found

Paint is a queer disabled artist and poet, in the never ending process of healing PTSD and discovering new ways to create and live authentically. They have an educational background in disability studies and he currently lives fun-employed as a full-time disabled person unmasking and rediscovering safety in life. You can find Paint's main website, with links to their art and merch, here: https://paint.gay/index.html

John teaches writing at, among other places, a shelter for unhoused people.

Of course, “hostile design”—such as intentionally putting dividers on outdoor benches to make it impossible to sleep on them—is often directed at unhoused people, but it is emphatically not design by and for them.

I think it’s also important to note that how much stuff is “too much”—even accepting minimalism on its own terms—is entirely relative to how much space you have in which to put your stuff. The amount of stuff an unhoused person can keep in a grocery cart may look like “hoarding,” but it would feel quite sparse even in a very modest studio apartment. The more space you have, the less stuff you can seem to have, which is yet another way minimalism can be a shell game of privilege.