The Work of Liberation is Also Chicken Stew

weaving and reweaving the fabric of community is quiet, quotidian, Sisyphean work

There’s a lot of talk these days in radical activist circles about being in community while doing the work of liberation—especially in the context of protest against the ongoing genocide being perpetuated by the state of Israel against the Palestinian people in Gaza and the West Bank.

On social media, you can find many posts sharing ways we can be involved in this protest, especially as disabled people who must both balance our very real needs while also stretching our capacities and tolerances in the face of a real-time genocide unfolding through windows in the palms of our hands as Jesse so eloquently put it. Devon Price, especially, has been generous and eloquent in sharing ways to get involved, as well as reflections on his own growing experience of solidarity and community in the midst of his activism.

While we are urged to do all of this “in community,” there is much less talk about the quotidian reality of creating the very fabric of the community in which liberation can be cradled.

I have a lifetime of marching (beginning as a toddler marching against the Vietnam War) for all sorts of causes and against all sorts of atrocities. And while I am in awe of and deeply inspired by the rich, urgent Palestine liberation activism happening now in streets, shipyards, and munitions plants, shutting down trains, bridges, and boulevards, interrupting politicians and propaganda and Thanksgiving Day parades—I think it’s also important to talk about what it really means to “be in community”—not just in the immediate context of urgent protest, but in the long run.

Because this is a long game, folks. I’ve been alive long enough to know that things can change, but also that the work of liberation is never done. I never thought I would see the world rise up in support of Palestinian lives, just like I never thought I would see marriage equality (which, paradoxically, made it possible for me to divorce), or the fall of apartheid in South Africa1; sadly, the current war on trans people and the stark and racialized wealth disparities that continue to this day in South Africa are far less surprising.

Change is possible, but it is only ever partial. Liberation is a daily practice, not a destination. We have to find ways to make doing liberation sustainable in the long-term, and I believe that the quiet, daily, often invisible work of making community is at the heart of it.

In the Christian scriptures, there is a story about the sisters Mary and Martha (Luke 10:38-42)that is often pointed to by progressive Christians as an example of Jesus’s feminism. In this story, when Jesus visits Mary and Martha’s home in a village known in the Christian Bible as Bethany, which is today the Palestinian village of Al-Eizariya, Mary sits at Jesus’s feet, presumably the lone woman among a group of men listening to Jesus speak. Martha, on the other hand, is busy with “many tasks” and complains to Jesus that Mary has left her to do all the work herself. Jesus responds, “Martha, Martha, you are worried and distracted by many things, but few things are needed—indeed only one. Mary has chosen the better part, which will not be taken away from her.”

Feminists rightly celebrate Jesus’s embrace of Mary among the acolytes sitting at his feet, listening and learning. Still, this story has never sat quite right with me. Not just because I share her name, I think I have always over-identified with Martha—I feel a visceral resentment at that patronizing “Martha, Martha.” Jesus so blithely dismisses Martha’s work and her “many tasks” as the unnecessary “lesser part”—yet who does he think cleans the floor on which his merry band of followers sit at his feet? And when a meal arrives to feed them all, and a pitcher of water to quench their thirst, it was Martha’s hands and skill, not her “worry and distraction,” that prepared them.

In his beautiful essay Moments of Protest Devon Price writes about the generous welcome he is afforded at a Powwow he attended in Chicago, where he ate “chicken stew and chat[ted] with aunts about their family members’ health conditions”—and when I read that, my mind when immediately to the kitchen where the aunts are preparing the stew; to the doctor’s appointments, where they are holding a hand, taking notes, asking questions. At a protest march Devon writes: “This must be what people feel at church, I think, or at synagogue or the mosque”—and I am transported back to my decade and a half of Sunday School rally days, Christmas pageants, homeless shelter meals, and church retreats—the largely invisible work of (mostly) women “worried and distracted” by the unsung work of making a community where people can feel such things together.

In the face of genocide, it is definitely time to flood the streets and Shut Things Down —and it is also true that liberation can only ever take root in the rich soil of communities where we can rest and laugh and talk and listen and share meals—all of which requires a different sort of liberation work. If we learned anything from the activist fervor of the 1960’s, where the men did the “work” of revolution and the women were expected to cook the meals and clean up after—I hope we have learned that this is a false dichotomy, that this domestic work need not be gendered and is also the revolution.

And here I’m not just talking about the people doing the actual logistics of feeding and hydrating and housing and clothing the bold and brave activists in the streets, though that is absolutely crucial. I’m also talking about everyone who is tidying up their home for the holidays and trying to make it lovely, and inviting friends over for conversation and a home-cooked meal; I’m talking about making a sandwich when an unhoused neighbor knocks on the door; I’m talking about sharing tomatoes and peppers from the vegetable garden in your back yard and chatting with neighbors over the pollinator garden in your front yard; I’m talking about bringing soup to a friend who just had surgery and baking a gluten-free apple pie for the friend who is fitting out your micro-camper van so you can go on a road trip next summer and finally rest your eyes on beautiful landscapes that soothe your nervous system and fill you with enchantment and hope and joy … so you can return and do it all again.

The work of liberation is a street fight, but it is also chicken stew and Sunday School. In his video essay Nowhere to Go: The Loss of Third Places, Elliot Sang2 discusses the epidemic of loneliness that was already endemic to our society before the pandemic pushed many of us over the edge. Sang points to sociologist Ray Oldenburg’s notion of the “third place”—not home, not work, but a brick and mortar space for informal social interaction—a neighborhood cafe, a pub, even a post office or drugstore. Such places, especially ones where it is possible to mix across classes and generations, are increasingly rare, and more and more, people feel alone and friendless with nowhere to find, much less be in, community with neighbors and friends.

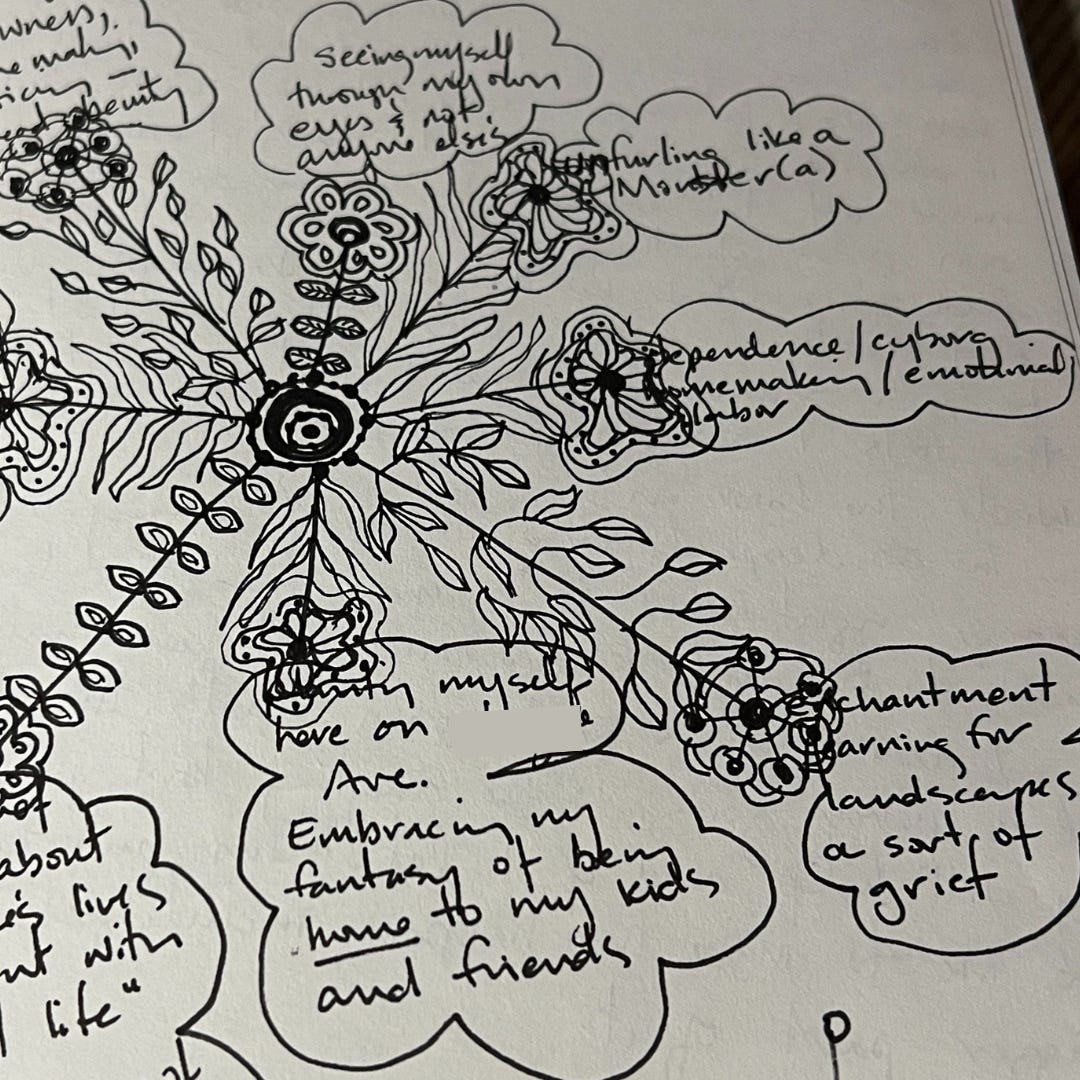

I had never encountered the words “third place” for this concept, but I immediately realized that for much of my adult life, my home was that third place for so many friends and neighbors (before I lost all that in my divorce; divorce is brutal, not just for couples and families but for whole communities). I recently came across a journal/doodle entry in which I recognized I was grieving those losses and challenged myself to embrace my dream of once again making my home a vibrant place for people to gather in community. This work suits my nervous system better than street activism, though it definitely still stretches me, especially as I become less masked and more and more inclined toward being a hermit.

The world we are dreaming of and striving for needs street activists who take up arms against injustice, but it also needs Marthas, profoundly and crucially; to weave and reweave the fabric of community is quiet, quotidian, Sisyphean work, but without it, revolution and liberation will never grow roots and bear fruit.

This work may be quiet and quotidian, but it is is not simple or easy, especially for those of us who find social situations and spaces a sensory challenge that can be as depleting as they are life-giving. In my former life, alcohol served as a buffer in what ultimately became quite unhealthy ways. The relentlessness of my social life then often left me agonizingly anxious and burned out, which mostly undid any of the positive aspects of “being in community.” Now, I do find it challenging to design new ways of doing community that takes disability justice seriously (everything happens so late! and is usually awash in alcohol….), but I am committed to iterating. This is my work.

In another essay soon (because this one has gotten quite long enough!) I want to be more transparent about the challenges I face as a neurodivergent disabled person in doing this sort of community-building liberation work, and also some of the ways I’m trying anyway, even though they don’t always work, and what I dream future iterations might look like.

I’d love to hear from you in the comments—do you find loneliness and social isolation a problem? Do you have “third places” where you can connect with neighbors and friends? What are the challenges you face to building, nurturing, and being in community?

When I was in college we used to have dances where we would scream and shout and jump up and down to the song “Free Nelson Mandela” with literally no thought that it would ever actually happen, much less that he would become President.

I wasn’t familiar with Sang’s YouTube channel until he interviewed Jesse for his latest video, ADHD: A Nightmare Under Capitalism, which is very good and you should definitely go watch it! I’m looking forward to watching more of his videos.

I really resonate with trying so hard to stretch to build community as unmasking makes it difficult and overstimulating to be around a lot of people!! I’m also trying to find the balance of that myself. I also still take COVID precautions as it is a disabling virus and it’s difficult to find folks who are still taking precautions as well.

This essay is a deep breath that speaks to everything I’ve already known and am so happy to see affirmed so beautifully in your writing. Thank you.